Known for her comedic roles, Hong Kong actress-director Sandra Ng has also had her fair share of serious roles. With her directorial debut Goldbuster released last year, Ethan Yeo takes a look at the evolution of her career.

The gambling savant is helplessly in love. The enigmatic beauty, we learn during a graceful farewell wave, has a mole on her armpit. In her absence, he is paralysed by lovesickness. Serendipitously, Ping has an identical mole. She swaggers into the room with her right arm raised, parading the all-important mole. The reinvigorated savant and the ersatz subject of affection go on a date. He talks gently to the armpit mole as fellow diners at the restaurant gawk, dumbfounded. Comedy is farmed from Ping’s obvious exasperation, not from embarrassment but from the fatigue at having to raise her arm continuously. – All for the Winner (1990)

One of the top-grossing actresses of Hong Kong’s film industry today, Sandra Ng is most renowned for her lowbrow comedic roles in the 1980s, that are abundant with crass gags involving tempestuous hags and inopportune loud farts. She was highly prolific, appearing in a wide variety of films ranging from police cadet capers (The Inspector Wears Skirts; 1988) to rambunctious horror-comedies (Operation Pink Squad II; 1989), making her one of the most fondly recognized names in Hong Kong cinema.

But it wasn’t so happy-go-lucky behind the scenes back then. “During that time, when I was taking on the jester supporting roles, I sometimes wondered how my parents felt,” Sandra revealed in a 2017 television interview and a rare reminiscence of that period. The confessional interview with television host and ‘China’s Oprah’, Chen Luyu, had Sandra chronicling her early struggles with her career picks: “It is not anything to be ashamed of, but parents would usually want to see their daughter playing the leading character or princess roles; hence, when my parents attend the premieres of my movies and see me play uncouth nose-digging characters, they might hesitate to invite their relatives and friends to support the movies,” said Sandra.1

“She told me that the audiences in China only remember me as Stephen Chow’s sidekick and are not familiar with Sandra Ng beyond reruns of classics on evergreen channels.”

Yet, it was precisely this bravado in embracing such jester roles that carved Sandra a niche in the industry and formed the foundation for her career’s longevity. “Despite those concerns, I realised that these nose-digging roles had more character and evoked more feelings,” she added.

In the Hong Kong entertainment industry back then, celebrities who displayed range and versatility were rewarded with more varied acting opportunities, opening the gates for bigger pay checks and stature in the industry. However, Sandra’s early attempts at roles with dramatic heft were met with muted response in comparison to her other films released in the same year. Thunder Cops II (1989) saw Sandra playing an undercover policewoman set on avenging her late father only to get herself framed for murder. This rare dramatic role for her saw the film collecting only HK $5.6 million. In comparison, the comedies she starred in, Operation Pink Squad II and Vampire vs Vampire, scooped up more than HK $11 million each at the box office.2

It was the heyday of the frantically productive Hong Kong film industry then and pragmatic film investors were unforgiving toward films that did not register particularly well with the audiences. Sandra did not partake in non-comedic roles anymore for the next few years, but the ugly jester persona took a toll on her ego and she decided to undergo an image revamp. “After acting in these roles for five years, from 1987 to 1992, I felt I had enough. I was determined to change my image to a more beautiful Sandra Ng. I lost weight and stopped acting for two years. I just wanted to transform myself and out of the image of Sandra Ng that everyone else had defined me as. So I cut my hair, lost weight, even sang and made albums and shot arthouse films. Then I got the award,” Sandra told Chen.

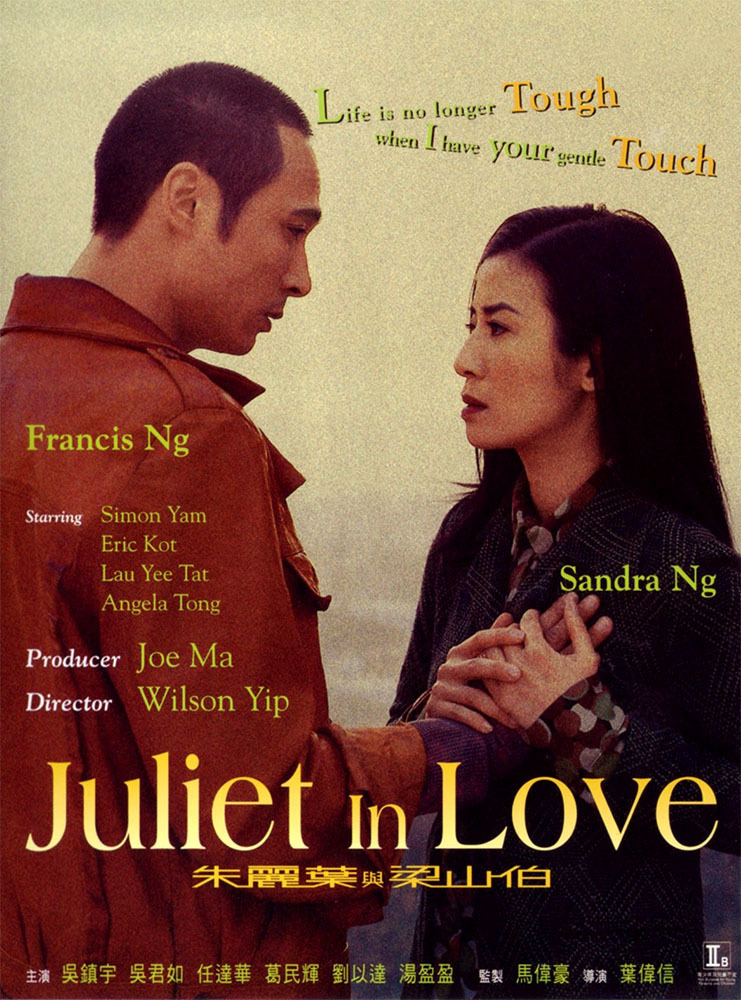

Judy unbuttons her blouse to show him that she has had a mastectomy. She does not see herself as a complete woman nor does she expect him to. They both lead such wretched existences; is it too much to dream of having each other to lean on and to form a family together? – Juliet in Love (2000)

The mid 1990s was generally a sombre period for Hong Kong as pre-1997 handover anxieties loomed. It was also this period that Sandra reignited her attempt at dramatic roles, from the atmospheric horror film The Returning (1994) to the self-funded experimental omnibus Four Faces of Eve (1996). Her efforts earned her several acting award nominations, culminating in her first Best Actress win at the 18th Hong Kong Film Awards for Portland Street Blues (1998). Playing a reticent lesbian pimp flexing her power in the triads, her understated delivery impressed both critics and audiences and staked her a place in the iconic Young and Dangerous film series.

This acting award was hitherto the biggest achievement in her life then, as Sandra mentioned in subsequent interviews. Sandra was at that point experiencing a sense of insecurity: she was past thirty, single with no kids, and had been acting for 17 years. Winning an award was equivalent to an actor making a mark in the industry’s history, and would open doors to better opportunities as well as more stature among the industry, the media and audiences.

As Sandra continued to juggle comedy with drama, she also plunged herself into her most depressing role to date in Juliet in Love (2000). Exhibiting exceptional emotional depth, Sandra played a lonely cancer survivor bonding with a junior triad member, striving for domestic bliss through a makeshift family unit, only to have her hopes cruelly shattered. While the relentless tragedy of the characters’ predicaments is arguably manipulative, the film stood out for unprecedentedly sensitive performances from Sandra and Francis Ng.

As a long time fan of Sandra’s, I sometimes wonder how much of Sandra’s personal emotions colour her performance. Her increased attempts at serious roles betray a comedian’s fatigue, and isn’t the dark inner world of comedians more fascinating than their comedy? My curiosity at how much of her real life psychological states she blends into her performances continued in the 2000s.

With gusto, Kam elaborately performs Jackie Chan’s ‘drunken fist’ martial art moves in her golden gown, amidst noisy chatter in the nightclub. Is it bitter for a dance hostess to discard her feminine dignity to be a clown? Perhaps, but she understands perfectly that she lacks physical beauty, therefore she must prove her relevance to earn her keep. It is the 1980s. Everyone is rolling in cash and dignity is all but buried under her facade of overdone cheerfulness. – Golden Chicken (2002)

It is precisely this understanding which parallels her early stage career that makes Golden Chicken (2002) so compelling. Lacking the conventional physical beauty of her peers, Sandra Ng as Kam gamely becomes the jester by owning her roles with aplomb and bestowing them with dignity by proudly wearing on her sleeves the aspirations of the hoi polloi. It is this adroitness at injecting heart into the madcap that garnered her the rare feat of winning a major acting award for a comedic role.

The film was also notable for its purposeful portrayal of Hong Kong’s identity amidst heavy social dialogue post-1997 handover – the beginning of a trend in which Sandra started mixing her comedy with social consciousness. Golden Chicken 2 (2003) tracked the anxieties of Hong Kongers during the SARS epidemic and showcased Hong Kongers’ ‘never say die’ resilience. My Life As Mcdull (2001) and the ensuing sequels (2004-2016) rued the rapid changes of Hong Kong and the ending of an era.

The three men put on vampire costumes, wanting to trick the tenants into believing the estate is haunted and be spooked enough to move out of the premises themselves. The plan backfires when they find themselves trapped in a lift carriage with Ling. Mistaking Ling to be a ghost back to avenge her unjust death, they perspire in terror as Ling dressed in a creepy ancient Chinese brocade robe raspily interrogates them. Ling clearly enjoys the irony: she has come here to perform an exorcism yet now finds herself pretending to be a ghost, scaring off bullies who are attempting to achieve monetary gains by devious means. – Goldbuster (2017)

With the commercially troubled climate of the Hong Kong film industry following the handover, most Hong Kong film productions found themselves needing Chinese financing or collaboration in order to pull in sustainable profits.3 As evidenced from chatter in popular magazines and online forums like Golden, many fans of Hong Kong films continue to be dismayed to find that these pan-Chinese collaborations demand compromises to suit China’s taste and policies.

In Sandra’s directorial debut Goldbuster (2017), tributes were boisterously paid to popular horror film motifs like malevolent spirits, vampires, and zombie attacks, before exposing these supernatural occurrences to be fabrications by characters in the film. The emphasis on the non-existence of real ghosts is a small irony, considering the importance of ghosts in the heyday of Hong Kong’s film industry and Sandra’s early career when she starred in 16 horror-comedies between 1989 and 1992.

However, the emphasis is perhaps necessary, for Goldbuster is funded by Chinese investors, and China does not allow for screening of films that promotes superstitions or pseudoscience feudalistic ideology and has gained a notoriety for banning films that portray ghosts to be real.4Evil ghosts have also been known to be used as metaphors for corrupt government officials throughout Chinese literature and folklore, thus the Chinese government’s ban on ghost stories may be seen as a measure to control socio-political critique.5

As a long time fan of Sandra’s, I sometimes wonder how much of Sandra’s personal emotions colour her performance. Her increased attempts at serious roles betray a comedian’s fatigue, and isn’t the dark inner world of comedians more fascinating than their comedy?

During the film’s premiere in China, Sandra shared that she took on this project partly because of encouragement from her famous producer spouse Peter Chan during a conversation on her capability to connect with the masses with new works instead of capitalising on her comedienne persona. She also recounted a chat with a young manicurist in China as instrumental: “She told me that the audiences in China only remember me as Stephen Chow’s sidekick and are not familiar with Sandra Ng beyond reruns of classics on evergreen channels.”6 This evoked in Sandra a desire to direct her own film.

With shadows of an ode to Sandra’s early career, the bulk of the comedy in Goldbuster stems from the conflicts between an unscrupulous property developer, the tenants he attempts to oust, and the mercenary swindler sandwiched between both parties. Familiar themes are abundant in this pastiche of 1980s Hong Kong films: a motley crew uniting to overcome a crisis together, resilience in the face of adversity, (sense of) home ownership being challenged by redevelopments, penance for betrayal of friendships, the proletariat battling against powerful, unfeeling large corporations. So what if the hilarity of the gags may waver unevenly, and plot coherence is at times merrily sacrificed for exuberant chase sequences? The real genius of Goldbuster and perhaps Sandra Ng is using a Chinese film to keep the Hong Kong spirit alive.

Ethan Yeo is a translator when he is not embarking on filmic flights of fantasies. He co-produced Asian Film Archive’s Singapore Shorts Vol. 2 DVD anthology.

Want a good laugh? Maybe it’s time to witness another side of Sandra Ng beyond armpit hair gags and fart jokes. Her directorial debut, Goldbusters is now available on A Little Seed here!

2 http://hkmdb.com/db/movies/view.mhtml?id=7183&display_set=eng

3 A 2016 research report by the Legislative Council of Hong Kong indicates co-productions between Hong Kong and mainland studios account for more than 50-percent of films produced in Hong Kong in recent years. “Co-produced movies are generally better received in local box office, due in part to bigger production budget and more attractive cast. In 2014, there were 27 co-produced movies screened in Hong Kong, commanding a combined box office of HK$234 million, twice the respective sum of HK$115 million for those 23 local movies produced by Hong Kong companies,” stated the report. From: https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/essentials-1516ise13-challenges-of-the-film-industry-in-hong-kong.htm#endnote7

4 Films banned from theatrical release in China that may fall under this category include Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006), Crimson Peak (2015) and Ghostbusters (2016).

5 https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35008573

6 https://www.sohu.com/a/212985329_114941